English followed by une version en français y una versión en español.

I note that I myself, though a-religious, find great pleasure in playing old hymns on the piano. And in the process I have come across one of the most famous Negro spirituals: Were You There? I would struggle to put into words what makes this such a great song. Among other things, it seems to have something to say today, in this Trump era. As if he, the President, had not been there? Or as if now is yet another time in which the Lord is, once again, being crucified?

Many famous singers, Paul Robeson most notably, have recorded this song, but I’ve found only one recording I like, and it is sublime: Sam Cooke’s recording with The Soul Stirrers. Among other excellent things, Cooke, the son of a Baptist minister, changes the last line from the usual “were you” to “I was”: “I was there when they crucified the Lord.”

English

24 February 2025

From time to time he was getting up from the piano to test his blood pressure. 145, already much higher than his normal reading, but this evening it kept mounting: 160, 180, 200!

From time to time he was getting up from the piano to test his blood pressure. 145, already much higher than his normal reading, but this evening it kept mounting: 160, 180, 200!

He’d already had a quadruple bypass years ago, and when he was in the hospital back then, a senior cardiologist came to chat with him before the surgery. He’d told this doctor that, based on his family history, he’d always imagined he’d live to 90 and that the problem would be not running out of money before then. The doctor said that, given the state of his arteries, perhaps he should set his sights on 75 instead.

Seventy-five or, it seemed as he played the piano, perhaps just 70. Perhaps this was it. His body had given out.

He was enjoying playing and playing well. Bach, old French songs, Christmas carols, “O Come, All Ye Faithful”—

Sing, choirs of angels, sing in exultation,

Sing, all ye citizens of Heaven above!

He seemed to be getting better at reading music, at being able to play a piece he had not played in a while and to play the two hands at once, reading the score.

He had nary a thought of the global political and environmental wreckage. A writer by trade, it seemed to him that over the past 50 years he’d written enough; it would be no great loss to not be able to write anything more. This is what he would miss: being able to play the piano and to keep making progress.

To no end, in a certain sense. He was far, far technically from being a professional musician. Nor did he like performing. For him, it was just playing the notes, hearing the sounds coming through his headphones from his electric keyboard, learning new pieces. “Music,” he had recently read, “deals minutely in frustrations and fulfilments of desire.”

He had purchased a book of Czerny exercises to replace another left behind years ago. What he liked about Czerny was the lovely harmonies in which the exercises for eyes, mind and fingers were set out. As generations of piano students before him had known, he knew when he’d made a mistake: the sound was not fulfilling.

A reader of the present text might ask: what about the people he was going to be leaving behind? What about his beloved son, for all he and his son were now living three thousand miles apart? Or was it the fact of their separation that was keeping him from thinking about his son? In any case, he was now going to be able to leave him a nice sum of money. All he had to do was concentrate on his playing.

And clearly his enthusiasm for piano playing and also for continuing to develop his skills as a tennis player were signs of a strong will to go on living. And what a strange thing that seemed to be: a will to live so that he could hit a ball more consistently, accurately, strategically, and continue to play a musical instrument by himself, for himself.

Note

The citation about music comes from a Kenneth Burke essay on Psychology and Form. Best known as a literary theorist, Burke (1897–1993) also wrote music reviews (as well as poems and novels). Please note that the version of “Psychology and Form” linked above is from the original 1925 version, which does not include the passages given below. These latter are from the version of the essay that appeared in a later edition of the essay, published in the Burke essay collection Counter Statement.

And, at least in one version, Burke’s comment comes with this footnote regarding music frustrating and fulfilling desire: “modern music has gone far in the attempt to renounce this aspect of itself. Its dissonances become static, demanding no particular resolution.”

Français

24 février 2025

De temps en temps, il se levait du piano pour mesurer sa tension artérielle. 15, déjà beaucoup plus élevée que d’habitude, mais ce soir, elle n’a cessé d’augmenter : 16, 18, 20 !

Il avait déjà subi un quadruple pontage il y a des années, et lorsqu’il était à l’hôpital à l’époque, un cardiologue chevronné était venu discuter avec lui avant l’opération. Il avait dit à ce médecin que, compte tenu de ses antécédents familiaux, il avait toujours pensé qu’il vivrait jusqu’à 90 ans et que le problème serait de ne pas se retrouver à court d’argent avant. Le médecin lui a répondu que, vu l’état de ses artères, il devrait peut-être plutôt viser 75 ans.

Soixante-quinze ans ou, semblait-il pendant qu’il jouait au piano, peut-être seulement soixante-dix. C’était peut-être la fin. Son corps avait lâché.

Il prenait plaisir à jouer et à bien jouer. Bach, de vieilles chansons françaises, des chants de Noël, « O Come, All Ye Faithful »…

Chantez, chœurs d’anges, chantez dans l’exultation,

Chantez, vous tous, citoyens des cieux d’en haut !

Il semblait s’améliorer dans sa capacité à lire la musique, à jouer un morceau qu’il n’avait pas joué depuis longtemps et de le jouer à deux mains, en lisant la partition.

Il n’avait pas la moindre pensée pour le naufrage politique et environnemental. Ecrivain de métier, il lui semblait qu’au cours des 50 dernières années, il avait suffisamment écrit ; ce ne serait pas une grande perte de ne plus pouvoir écrire quoi que ce soit. Ce qui lui manquerait, c’est de pouvoir jouer du piano et de continuer à progresser.

En vain, dans un certain sens. Il était loin, très loin, techniquement, d’être un musicien professionnel. Il n’aimait pas non plus se produire devant les autres. Pour lui, il s’agissait simplement de jouer les notes, d’entendre les sons de son clavier électrique dans ses écouteurs, d’apprendre de nouveaux morceaux. La musique, avait-il lu récemment, traite minutieusement des frustrations et des satisfactions du désir.

Il avait acheté un livre d’exercices de Czerny pour remplacer un autre qu’il avait laissé derrière il y a des années. Ce qu’il aimait chez Czerny, c’était les belles harmonies dans lesquelles les exercices pour les yeux, l’esprit et les doigts étaient présentés. Comme des générations d’élèves de piano avant lui, il savait quand il avait fait une erreur : le son manquait de satisfaction.

Un lecteur du présent texte pourrait demander : et ceux qu’il allait laisser derrière lui ? Son fils bien-aimé, alors que lui et son fils vivaient maintenant à cinq mille kilomètres l’un de l’autre ? Ou est-ce la séparation qui l’empêche de penser à son fils ? En tout cas, il allait maintenant pouvoir lui laisser une belle somme d’argent. Il n’avait que se concentrer sur la musique.

Et il était évident que sa passion pour le piano et son désir de continuer à développer ses compétences en tant que joueur de tennis témoignaient d’une forte volonté de continuer à vivre. Et quelle étrange chose que cette volonté : une volonté de vivre pour pouvoir frapper une balle avec plus de régularité, de précision, de stratégie, et pour continuer à jouer d’un instrument de musique par lui-même, pour lui-même.

Il y avait aussi des moments où il se disait que manifestement, grâce au piano et peut-être aussi aux progrès qu’il faisait au tennis, il avait encore la volonté de vivre. Et quelle étrange chose cela avait l’air d’être : une volonté de vivre simplement pour pouvoir continuer à jouer du piano par lui-même, pour lui-même.

Español

24 de febrero de 2025

De vez en cuando se levantaba del piano para tomarse la tensión. 145, ya mucho más alta que su lectura normal, pero esta tarde seguía aumentando: 160, 180, ¡200!

Hacía años que se había sometido a un bypass cuádruple y, cuando estaba en el hospital, un cardiólogo senior vino a hablar con él antes de la operación. Le había dicho a este médico que, basándose en sus antecedentes familiares, siempre había imaginado que viviría hasta los 90 años y que el problema sería no quedarse sin dinero antes. El médico le dijo que, dado el estado de sus arterias, tal vez debería fijarse en los 75 años.

Setenta y cinco o, según parecía mientras tocaba el piano, quizá sólo setenta. Tal vez había llegado el momento. Su cuerpo se había rendido.

Le gustaba tocar y tocaba bien. Bach, viejas canciones francesas, villancicos, «O Come, All Ye Faithful»…

Cantad, coros de ángeles, cantad exultantes,

Cantad, ciudadanos del cielo.

Parecía estar mejorando en la lectura de música, ser capaz de tocar una pieza que no había tocado en mucho tiempo y tocarla con las dos manos a la vez, leyendo la partitura.

No pensó lo más mínimo en el naufragio político y medioambiental. Escritor de profesión, le parecía que en los últimos 50 años había escrito suficiente; no sería una gran pérdida no poder escribir nada más. Esto es lo que echaría de menos: poder tocar el piano y seguir progresando.

En cierto sentido, sin ningún fin. Técnicamente estaba muy lejos de ser un músico profesional. Tampoco le gustaba actuar delante de los demás. Para él, sólo era tocar las notas, escuchar los sonidos que le llegaban a través de los auriculares de su teclado eléctrico, aprender nuevas piezas. La música, había leído recientemente, se ocupa minuciosamente de las frustraciones y satisfacciones del deseo.

Había comprado un libro de ejercicios de Czerny para sustituir a otro que había abandonado hacía años. Lo que le gustaba de Czerny eran las bellas armonías en las que estaban dispuestos los ejercicios para los ojos, la mente y los dedos. Como habían sabido generaciones de estudiantes de piano antes que él, sabía cuándo se había equivocado… El sonido carecía de satisfacción.

Un lector podría preguntarse: ¿qué hay de la gente que él iba a dejar atrás? ¿Qué hay de su amado hijo, aunque ahora él y su hijo vivían separados por cinco mil kilómetros? ¿O era el hecho de su separación lo que le impedía pensar en su hijo? En cualquier caso, ahora iba a poder dejarle una buena suma de dinero. Sólo tenía que concentrarse en tocar.

Y claramente su entusiasmo por tocar el piano y también por seguir desarrollando sus habilidades como tenista eran signos de una fuerte voluntad de seguir viviendo. Y qué cosa tan extraña parecía ser: una voluntad de vivir para poder golpear una pelota con más constancia, precisión y estrategia, y seguir tocando un instrumento musical por sí mismo, para sí mismo.

— Text(s) by William Eaton.

— Text(s) by William Eaton.

I believe it is common for the with-it Substack writer to append to her or his post a comment such as “XYZ is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.” But Montaigbakhtinian is not in search of financial support.

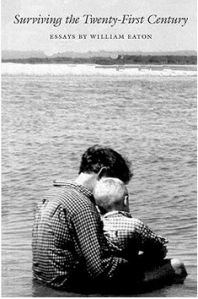

Interested readers are, however, certainly urged to check out William Eaton’s books, most available via Amazon and published either by Serving House Books or Zeteo Publishing. Among these books: Surviving the Twenty-First Century, a collection of personal essays (Serving House Books, 2015). The cover photograph, by Anne Fassotte, is a photo of William and his and Anne’s son. The photo was taken at Quansoo Beach, Martha’s Vineyard, circa 2003.

Salam, je souhaite travailler en Espagne dans l’agriculture, n’importe où, en construisant la moitié des rues dans l’agriculture. Je viens du Maroc et j’ai 29 ans.

Salam. La seule chose que je peux vous dire, à part bonne chance, est que je suis un fan du gouvernement socialiste de l’Espagne et il semble qu’il est prêt à offrir la bienvenue et l’emploi aux gens comme vous.