English followed by une version en français y una versión en español. There is also an extensive Notes section in English.

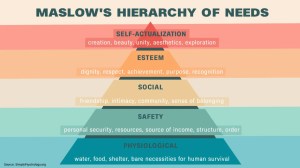

As Freud has been altered by psychologists and writers wishing that he had argued for what they themselves like to believe, so, too, it would seem with Abraham Maslow’s pyramid or hierarchy of needs. I find on the Web any number of bastardizations, from which I have selected the English, French and Spanish images below.

I pause to note an implication of this bastardizing of citations and ideas from prominent writers and other persons. The creator—Plato, for example, or Jane Austen, if you prefer—becomes a kind of mannequin on which almost any item of clothing can be hung. And this both as fashions change and in accordance with “my” particular preferences. If “I” wish to have Plato supporting me in my advocacy of lower taxes on the rich, or Austen joining me in condemning the patriarchy, the mannequins are right at hand, available for use. And I can dress them in clothes they themselves never wore or dreamt of wearing. And this “dressing” can include putting in quotes things the people attached to the names attached to the mannequins never said or wrote or dreamt of saying or writing. (And this particularly in Plato’s case since the earliest extant copies of copies of copies of “his” dialogues come from the ninth century AD, more than 1,200 years after the original Plato, let’s call him, died.)

English

Lost illusions

One Friday evening I was awaiting a response from a potential lover. It never came of course, but while waiting for it, I decided to go to the movies. In one of the second-run movie houses of my Paris neighborhood, I ended up watching That Uncertain Feeling, a 1941 Hollywood movie directed by Ernst Lubitsch. In this movie, a young New York wife and socialite finds herself curiously dissatisfied with her very comfortable life and her very stable and money-making husband, an insurance salesman. She has trouble sleeping and has developed a slight psychosomatic symptom.

She goes to see a psychoanalyst, and one day in the doctor’s waiting room she meets an eccentric, and indeed unpleasant, though highly talented pianist. He introduces her to art and music, she begins to take piano lessons. The pianist is of course interested in something more than this, and in the middle of the movie the woman—played by the very lovely Merle Oberon—is living with the pianist in her luxurious Park Avenue apartment. Her husband—ever the crafty salesman—has decided that to win her back he should first be generous, and thus proposes a divorce settlement that would leave her quite comfortable.

She goes to see a psychoanalyst, and one day in the doctor’s waiting room she meets an eccentric, and indeed unpleasant, though highly talented pianist. He introduces her to art and music, she begins to take piano lessons. The pianist is of course interested in something more than this, and in the middle of the movie the woman—played by the very lovely Merle Oberon—is living with the pianist in her luxurious Park Avenue apartment. Her husband—ever the crafty salesman—has decided that to win her back he should first be generous, and thus proposes a divorce settlement that would leave her quite comfortable.

The movie was not commercially successful, and watching it in 2025—and being myself an artist rather than a salesman—I thought it would have been more engaging if it had told of Ms. Oberon’s attempts, post-divorce, to make a new and more artistic life for herself. Of course she would not stay with the obnoxious pianist, but he would have set in motion a new life of self-exploration, cultural enrichment and, perhaps, sexual pleasure.

The 1978 movie An Unmarried Woman comes to mind as does Tessa Hadley’s novel of the Sixties, Free Love. I also recall a woman I knew in New York some time ago. In the late Sixties, a blonde, buxom and naïve Stanford grad freshly come to the big city, she fell into the lap of a Wall Street wheeler-dealer. One of the lesser of his shady financial dealings: he had my future friend, at the time his wife, invest in art which was paid for from business accounts while the works themselves where transferred to the family’s homes. In the process, the woman became an art historian, and, when I met her, she was at least semi-divorced and teaching at a well-known New York art institute. And in the interim—between the businessman husband and me—there had indeed been an artiste, an apparently very talented painter who was also an addict of some sort.

So should I also say something here about the “potential lover” I was waiting to hear from? Probably not. And, sadly, no sooner had the lovely Merle Oberon been tricked into thinking her estranged husband had found a good next lover than she went running back to him. And she took along with her snapshots of the wonderful early days of her and her husband’s wonderful romance. And this notwithstanding how hard it was going to be for at least one viewer to imagine that such a charming young woman had ever found the least delight with such a boring, money-enveloped man.

Some weeks later I happened to read a chapter on male and female roles in England in the seventeenth century. The author stated: “It is the overriding assumption of the conduct books and guides to godliness current in the 1660s that it is a woman’s lot to become a wife and that her self-fulfillment is to be found in the faithful and obedient performance of that role.”

We might say that this begins to describe the lot of a woman on Park Avenue, New York in the early 1940s. But the historian went on to propose that in seventeenth-century England women were thought to be more in the throes of sexual desire than men, and further it was thought that female orgasm warmed the womb and thus promoted successful conception. (And thus those English were not far from the contemporary feminist idea that men have a duty to attend to women’s sexual pleasure.)

A light went on in my dim mind! There was a key aspect—the key aspect!— of the movie that I had been entirely overlooking! In Merle’s brief conversation with the psychoanalyst it had come out that her husband was a very sound sleeper, whereas she was not. And there was a scene of the married couple, in the middle of the night, in their separate, almost-touching beds. Merle struggles to rouse her husband, but he is quickly back to sleep.

It occurred to slow me that this was Lubitsch’s (1940s Hollywood) way of indicating that the marriage was lacking in sex, and that a lack of sexual fulfillment or release might have been the cause of Merle’s dissatisfaction and of the psychosomatic hiccups that had led her to see a psychoanalyst.

And this then leads to the next point: the couple has no children, and there is not even any discussion of possibly having them (or of having sex). A friend with whom I was corresponding about the movie asked if the husband might have been homosexual, but I don’t think so. In contemporary parlance we could say he was “asexual.”

I return to my history of seventeenth-century England: “[I]t was assumed that any wife desired children. Through childbearing the curse on Eve [i.e. on women] is reversed, for the pains of labour issue in the blessing of children through which salvation becomes possible.”

Thanks to the psychologist Abraham Maslow and his famous (and individualitic) hierarchy of needs, for “salvation” we could substitute “self-actualization.” And in more than one previous essay I have proposed that for most contemporary adult humans, female and male (and myself included), parenting is a much more interesting, engaging and ambitious activity than those activities offered by businesses or other employers. (Or than the social whirl a wealthy man’s wife may get caught up in?)

Thanks to the psychologist Abraham Maslow and his famous (and individualitic) hierarchy of needs, for “salvation” we could substitute “self-actualization.” And in more than one previous essay I have proposed that for most contemporary adult humans, female and male (and myself included), parenting is a much more interesting, engaging and ambitious activity than those activities offered by businesses or other employers. (Or than the social whirl a wealthy man’s wife may get caught up in?)

It is decades since I have read the first word of Maslow’s, but did he overlook how an individual’s self-actualization—or voyage of self-discovery, I’d like to call this—could involve helping others—children—make their way onto a path toward self-actualization?

From this perspective, in the movie Merle doesn’t need art or music, she needs womb-warming sex!

More soberly, we may note the interesting question the movie raises though does not explore: whether, in the good ol’ days, a woman who appeared to have it all—money, social status, youth and good looks—could in fact lead a fulfilling, self-actualizing life? Which is also to underscore that one’s potential to self-actualize may depend a great deal on one’s social class (gender included here). (I find myself interested, in this regard, by the lives of partners of professional tennis players and other star athletes.)

Money does not seem the key factor. Today, as in the past, many well-off women and men seem willing to sacrifice a great deal for the security and pride of appearing to have achieved the kind of financial success and social status that is symbolized by Oberon’s very spacious Park Avenue apartment. This is hardly the self-actualization Maslow had in mind.

To close, I will note that since my “potential lover” was married to some kind of businessman, and since she herself had had some sort of business career . . . I could not help thinking that Oberon’s lily-livered return to her husband was a sign of the futility of my own suit. Via the movie the gods were trying to tell me something. For the French-subtitled version of the film that I watched, the title was Illusions perdues (Lost illusions).

Six notes

[1] Long ago the writer Nicholas Delbanco proposed to me that all novels had one of two plots: either a stranger comes to town or someone sets out on a voyage. In That Uncertain Feeling a stranger—the pianist—comes to town, but I would have preferred watching Ms. Oberon set out on a voyage. This thought occurred to me when I was reading Vicki Baum’s excellent novel Berlin Hotel (or Hotel Berlin) which includes a young actress, a star of the Berlin stage in 1943, being confronted by a young man dedicated to freeing the country from the Nazis. I translate back into English from two passages of a French translation of the novel:

[1] Long ago the writer Nicholas Delbanco proposed to me that all novels had one of two plots: either a stranger comes to town or someone sets out on a voyage. In That Uncertain Feeling a stranger—the pianist—comes to town, but I would have preferred watching Ms. Oberon set out on a voyage. This thought occurred to me when I was reading Vicki Baum’s excellent novel Berlin Hotel (or Hotel Berlin) which includes a young actress, a star of the Berlin stage in 1943, being confronted by a young man dedicated to freeing the country from the Nazis. I translate back into English from two passages of a French translation of the novel:

[T]his famous star so astonishingly popular . . . had never had time to grow up and was still living, as it were, in the fairytale world of her childhood.

As this was the first time she had thought alone and by herself, it was hard work. Her untrained mind had a hard time discerning lies from truth and right from wrong.

[2] The actress is at this time rehearsing to play Portia in a German version of The Merchant of Venice, and at several points in the novel Baum quotes from Portia’s speeches, to include these lines in which Portia speaks to and of herself:

But the full sum of me

Is sum of something, which, to term in gross,

Is an unlessoned girl, unschooled, unpracticed;

Happy in this, she is not yet so old

But she may learn; happier than this,

She is not bred so dull but she can learn; . . .

[3] Among my essays on parenting: What shall I learn of parenting or parenting of me? which was written in 2012, when my son was 12. Another: Nurture, which was posted on Montaigbakhtinian in 2017. (And for more on Plato, one might see my Friendship, Decepiton, Writing Within and Beyond Plato’s Lysis, originally published in Agni in 2019.)

[4] Some readers may find of interest this article about Merle Oberon: ‘She had to hide’: the secret history of the first Asian woman nominated for a best actress Oscar (by Andrew Lawrence, The Guardian, 7 March 2023).

[5] N.H. Keeble, The Restoration: England in the 1660s (Blackwell, 2002).

[6] Mr. Keeble being a literature professor and his subject being England in the seventeenth century, he finds several occasions to quote from Milton, to include these lines from the Satan of Paradise Lost:

Sight hateful, sight tormenting! thus these two

Imparadis’t in one anothers arms

The happier Eden, shall enjoy thir fill

Of bliss on bliss, while I to Hell am thrust,

Where neither joy nor love, but fierce desire,

Among our other torments not the least,

Still unfulfill’d with pain of longing pines; . . .

Français

Illusions perdues

Un vendredi soir, j’attendais une réponse d’une maîtresse potentielle. La réponse n’est jamais venue, bien sûr, mais en l’attendant, j’ai décidé d’aller au cinéma. Dans l’un des cinémas de rediffusion de mon quartier parisien, j’ai regardé « That Uncertain Feeling », un film hollywoodien de 1941 réalisé par Ernst Lubitsch. Dans ce film, une jeune mondaine new-yorkaise se trouve étrangement insatisfaite de sa vie très confortable et de son mari très stable et prospère, un vendeur d’assurances. Elle a du mal à dormir et a développé un léger symptôme psychosomatique.

Elle consulte un psychanalyste et, un jour, dans la salle d’attente du médecin, elle rencontre un pianiste excentrique, voire désagréable, mais très talentueux. Il l’initie à l’art et à la musique, et elle commence à prendre des leçons de piano. Le pianiste est bien sûr intéressé par quelque chose de plus que cela et, au milieu du film, la femme – interprétée par la très belle Merle Oberon – partage son appartement luxueux de Park Avenue avec le pianiste. Son mari – toujours un vendeur rusé – a décidé que pour la reconquérir, il devait d’abord se montrer généreux, et il propose donc un accord de divorce qui la laisserait à l’aise.

Le film n’a pas eu de succès commercial, et en le regardant en 2025 – et étant moi-même plutôt artiste que vendeur – j’ai pensé que le film aurait été plus intéressant s’il avait raconté les tentatives de Mme Oberon, une fois divorcée, pour se construire une nouvelle vie plus artistique. Bien sûr, elle ne resterait pas avec l’odieux pianiste, mais il aurait déclenché une nouvelle vie d’exploration de soi, d’enrichissement culturel et, peut-être, de plaisir sexuel.

Le film « An Unmarried Woman » de 1978 me vient à l’esprit, tout comme un roman de Tessa Hadley des années soixante, « Free Love ». Je me souviens aussi d’une femme que j’ai connue à New York il y a quelque temps. Dans les années 1960, une blonde, plantureuse et naïve diplômée de Stanford, fraîchement arrivée dans la grande ville, elle est tombée dans le giron d’un trafiquant de Wall Street. L’une des moindres de ses opérations financières douteuses : il a demandé à ma future amie, qui était à l’époque sa femme, d’investir dans des œuvres d’art qui ont été payées sur des comptes commerciaux alors que les œuvres elles-mêmes ont été transférées dans les maisons de la famille. Au cours de ce processus, la femme est devenue historienne de l’art et, lorsque je l’ai rencontrée, elle était au moins semi-divorcée et enseignait dans un institut d’art new-yorkais réputé. Et dans l’intervalle – entre le mari homme d’affaires et moi – il y avait bien eu un artiste, un peintre apparemment très talentueux qui était aussi toxicomane.

Dois-je également parler de la « maîtresse potentielle » dont j’attendais des nouvelles ? Probablement pas. Et, malheureusement, à peine la charmante Merle Oberon avait-elle été amenée à penser que son mari, dont elle était séparée, avait trouvé quelqu’un d’autre, qu’elle est retournée le voir en courant. Et elle a emporté avec elle des instantanés des premiers jours de la merveilleuse romance entre son mari et elle. Et ce, malgré la difficulté pour au moins un spectateur d’imaginer qu’une jeune femme aussi charmante ait pu trouver le moindre plaisir auprès d’un homme aussi barbant et consumé par l’argent.

Quelques semaines plus tard, j’ai lu un chapitre sur les rôles masculins et féminins en Angleterre au XVIIe siècle. L’auteur déclarait que les livres de conduite et les guides de piété de cette époque partent du principe que la femme est destinée à devenir une épouse et que son épanouissement se trouve dans l’accomplissement fidèle et obéissant de ce rôle.

Nous pourrions dire que cela commence à décrire le sort d’une femme à Park Avenue, à New York, au début des années 1940. Mais l’historien poursuit en indiquant que, dans l’Angleterre du XVIIe siècle, on pensait que les femmes étaient davantage en proie au désir sexuel que les hommes, et que l’orgasme féminin réchauffait l’utérus et favorisait ainsi une conception réussie. (Ces Anglais n’étaient donc pas loin de l’idée féministe contemporaine selon laquelle les hommes ont le devoir de s’occuper du plaisir sexuel des femmes).

Une lumière s’est allumée dans mon esprit obscur ! Il y avait un aspect essentiel – l’aspect essentiel – du film que j’avais complètement négligé ! Dans la brève conversation de Merle avec le psychanalyste, il était apparu que son mari dormait très bien, alors qu’elle ne le faisait pas. Et il y avait une scène montrant le couple marié, au milieu de la nuit, dans leurs lits séparés, qui se touchent à peine. Merle s’efforce de réveiller son mari, mais celui-ci se rendort rapidement.

Il m’est venu à l’esprit que c’était la façon dont Lubitsch (dans l’Hollywood des années 1940) indiquait que le mariage manquait de sexe, et qu’un manque d’épanouissement ou de libération sexuelle pouvait être la cause de l’insatisfaction de Merle et des hoquets psychosomatiques qui l’avaient amenée à consulter un psychanalyste.

Cela nous amène au point suivant : le couple n’a pas d’enfants et ne parle jamais de la possibilité d’en avoir (ou d’avoir des relations sexuelles). Un ami avec qui je correspondais à propos du film m’a demandé si le mari aurait pu être homosexuel, mais je ne le pense pas. Dans le langage contemporain, on pourrait dire qu’il était « asexué ».

Je reviens à mon histoire de l’Angleterre du XVIIe siècle et traduis : « On partait du principe que toute femme désirait avoir des enfants. » L’enfantement transforme la malédiction qui pesait sur Ève (c’est-à-dire sur les femmes) ; les douleurs du travail aboutissent à la bénédiction d’enfants grâce auxquels le salut devient possible.

Et grâce au psychologue Abraham Maslow et à sa célèbre (et individualiste) pyramide des besoins, nous pourrions remplacer « salut » par « auto-actualisation ». Et dans plus d’un essai précédent, j’ai proposé que pour la plupart des adultes contemporains, femmes et hommes (y compris moi), être parent est une activité bien plus intéressante, engageante et ambitieuse que celles proposées par les entreprises ou autres employeurs, et a fortiori par le tourbillon social d’une épouse d’un homme fortuné.

Et grâce au psychologue Abraham Maslow et à sa célèbre (et individualiste) pyramide des besoins, nous pourrions remplacer « salut » par « auto-actualisation ». Et dans plus d’un essai précédent, j’ai proposé que pour la plupart des adultes contemporains, femmes et hommes (y compris moi), être parent est une activité bien plus intéressante, engageante et ambitieuse que celles proposées par les entreprises ou autres employeurs, et a fortiori par le tourbillon social d’une épouse d’un homme fortuné.

Cela fait des décennies que je n’ai pas lu le premier mot de Maslow, mais a-t-il négligé le fait que l’auto-actualisation d’un individu – ou son voyage de découverte de soi, comme j’aimerais l’appeler – pourrait impliquer d’aider d’autres personnes – des enfants – à s’engager sur la voie de l’auto-actualisation ?

De ce point de vue, dans le film, Merle n’a pas besoin d’art ou de musique, elle a besoin de sexe qui réchauffe l’utérus !

Plus sobrement, on peut noter la question intéressante que le film soulève sans pour autant l’explorer : dans le bon vieux temps, une femme qui semblait tout avoir – argent, statut social, jeunesse et beauté – pouvait-elle en fait mener une vie épanouie et se réaliser ? Il convient également de souligner que le potentiel d’auto-actualisation d’une personne peut dépendre dans une large mesure de sa classe sociale (y compris de son sexe). (Je m’intéresse, à cet égard, à la vie des partenaires des joueurs de tennis professionnels et d’autres athlètes vedettes.)

L’argent ne semble pas être le facteur clé. Aujourd’hui, comme par le passé, de nombreux hommes et femmes aisés semblent prêts à sacrifier beaucoup pour la sécurité et la fierté de paraître avoir atteint le type de réussite financière et de statut social symbolisé par le très spacieux appartement d’Oberon sur Park Avenue. Cela est assez loin de l’auto-actualisation envisagée par Maslow.

Pour conclure, je noterai que puisque ma « maîtresse potentielle » était mariée à une sorte d’homme d’affaires, et qu’elle-même avait eu une quelconque carrière dans le monde des affaires… Je n’ai pas pu m’empêcher de penser que le retour d’Oberon à son mari était un signe de la futilité de ma propre poursuite. Par le biais du film, les dieux essayaient de me dire quelque chose. La version sous-titrée en français du film que j’ai regardé s’intitulait « Illusions perdues ».

Español

Ilusiones perdidas

Un viernes por la noche, esperaba la respuesta de una amante potencial. La respuesta nunca llegó, por supuesto, pero mientras la esperaba decidí ir al cine. En uno de los cines de repetición de mi barrio parisino, acabé viendo That Uncertain Feeling (Qué sabes tú de amor o Lo que piensan las mujeres), una película de Hollywood de 1941 dirigida por Ernst Lubitsch. En esta película, una jovencita de la sociedad de lujo neoyorquina se siente extrañamente insatisfecha con su vida tan cómoda y con su marido, un vendedor de seguros muy estable y que gana mucho dinero. Ella tiene problemas para dormir y ha desarrollado un ligero síntoma psicosomático.

Acude a un psicoanalista y un día, en la sala de espera del médico, conoce a un pianista excéntrico y desagradable, aunque de gran talento. Éste la introduce en el arte y la música, y ella empieza a tomar clases de piano. Por supuesto, el pianista está interesado en algo más que esto, y a mitad de la película la mujer -interpretada por la encantadora Merle Oberon- vive con el pianista en su lujoso apartamento de Park Avenue. Su marido, un vendedor muy astuto, ha decidido que para reconquistarla primero debe ser generoso, y le propone un acuerdo de divorcio que la dejaría bastante cómoda.

La película no fue un éxito comercial, y al verla en 2025 -y siendo yo más artista que vendedor- pensé que habría sido más interesante si hubiera contado los intentos de la Sra. Oberon, una vez divorciada, de construirse una nueva vida más artística. Por supuesto, ella no se quedaría con el odioso pianista, pero él habría puesto en marcha una nueva vida de autoexploración, enriquecimiento cultural y, tal vez, placer sexual.

Me viene a la mente una película de 1978 An Unmarried Woman (Una mujer descasada) así como una novela de Tessa Hadley de los años sesenta, Free Love. También recuerdo a una mujer que conocí en Nueva York hace algún tiempo. En los años sesenta, una rubia, pechugona e ingenua graduada de Stanford recién llegada a la gran ciudad, cayó en las garras de un estafador de Wall Street. Entre sus turbios negocios financieros: pidió a mi futura amiga, que entonces era su esposa, que invirtiera en obras de arte que se pagaban con las cuentas de la empresa, mientras que las obras se transferían a las casas de la familia. En el proceso, la esposa se convirtió en historiadora del arte y, cuando la conocí, estaba al menos semidivorciada y daba clases en un conocido instituto de arte de Nueva York. Y en el ínterin -entre el marido empresario y yo- había habido un artista, un pintor aparentemente de gran talento que también era drogadicto.

¿Debería también decir algo aquí sobre el «amante potencial» del que esperaba noticias? Probablemente no. Y, por desgracia, en cuanto a la encantadora Merle Oberon fue engañada haciéndole creer que su distanciado marido había encontrado a otra persona, volvió corriendo a su lado. Y se llevó consigo instantáneas de los primeros días del maravilloso romance entre ella y su marido. Y esto, a pesar de la dificultad por al menos un espectador de imaginar que una joven tan encantadora pudiera haber encontrado el más mínimo placer en un hombre tan aburrido y consumido por el dinero.

Unas semanas más tarde leí por casualidad un capítulo sobre los roles masculino y femenino en la Inglaterra del siglo XVII. El autor decía que el supuesto predominante de los libros de conducta y las guías de piedad de la época es que el destino de la mujer es convertirse en esposa y que su autorrealización se encuentra en el desempeño fiel y obediente de ese papel.

Podríamos decir que esto empieza a describir la suerte de una mujer en Park Avenue, Nueva York, a principios de la década de 1940. Pero el historiador continuó proponiendo que en la Inglaterra del siglo XVII se creía que las mujeres estaban más en la agonía del deseo sexual que los hombres, y además se pensaba que el orgasmo femenino calentaba el útero y por lo tanto promovía una concepción exitosa. (Y así, aquellos ingleses no estaban lejos de la idea feminista contemporánea de que los hombres tienen el deber de atender al placer sexual de las mujeres).

Una luz se encendió en mi mente oscura. Había un aspecto clave -¡el aspecto clave!- de la película que yo había pasado totalmente por alto. En la breve conversación de Merle con el psicoanalista había salido a relucir que su marido tenía un sueño muy profundo, mientras que ella no. Y había una escena del matrimonio, en plena noche, en sus camas separadas, casi tocándose. Merle se esfuerza por despertar a su marido, pero éste vuelve a dormirse rápidamente.

Se me ocurrió que era la forma que tenía Lubitsch (en el Hollywood de los años cuarenta) de indicar que el matrimonio carecía de relaciones sexuales, y que la falta de satisfacción o liberación sexual podía ser la causa de la insatisfacción de Merle y de el hipo psicosomático que la habían llevado a consultar a un psicoanalista.

Esto nos lleva al siguiente punto: la pareja no tiene hijos y nunca habla de la posibilidad de tenerlos (o de mantener relaciones sexuales). Un amigo con el que mantuve correspondencia sobre la película me preguntó si el marido podría haber sido homosexual, pero no lo creo. En lenguaje contemporáneo podríamos decir que era «asexual».

Vuelvo a mi historia de la Inglaterra del siglo XVII y traduzco: «Se asumía que cualquier esposa deseaba tener hijos. El parto transforma la maldición que pesaba sobre Eva [es decir, sobre la mujer]; los dolores del parto desembocan en la bendición de los hijos, a través de los cuales se hace posible la salvación.»

Gracias al psicólogo Abraham Maslow y su famosa jerarquía de necesidades, por «salvación» podríamos sustituir «autorrealización». Y en más de un ensayo anterior he sugerido que para la mayoría de los adultos contemporáneos, mujeres y hombres (incluida yo), la paternidad es una actividad mucho más interesante, atractiva y ambiciosa que las que ofrecen las empresas u otros empleadores. (¿O que el torbellino social en el que puede ser envuelta la esposa de un hombre rico?)

Gracias al psicólogo Abraham Maslow y su famosa jerarquía de necesidades, por «salvación» podríamos sustituir «autorrealización». Y en más de un ensayo anterior he sugerido que para la mayoría de los adultos contemporáneos, mujeres y hombres (incluida yo), la paternidad es una actividad mucho más interesante, atractiva y ambiciosa que las que ofrecen las empresas u otros empleadores. (¿O que el torbellino social en el que puede ser envuelta la esposa de un hombre rico?)

Hace décadas que no leo la primera palabra de Maslow, pero me parece posible que pasara por alto cómo la autorrealización de un individuo -o el viaje de autodescubrimiento, me gustaría llamarlo- podría implicar ayudar a otros -niños- a abrirse camino hacia la autorrealización.

Desde esta perspectiva, en la película Merle no necesita arte ni música, ¡necesita sexo que le caliente el útero!

Más sobriamente, podemos señalar la interesante cuestión que plantea la película, aunque no la explora: si, en los viejos tiempos, una mujer que parecía tenerlo todo -dinero, estatus social, juventud y buena apariencia- podía de hecho llevar una vida plena y autorrealizada. Esto también significa que el potencial de autorrealización de una persona puede depender en gran medida de su clase social (incluido el género). (En este sentido, me interesan las vidas de las parejas de los tenistas profesionales y otros deportistas estrella.)

El dinero no parece ser el factor clave. Hoy en día, como en el pasado, muchos hombres y mujeres acomodados parecen dispuestos a sacrificar mucho por la seguridad y el orgullo de parecer que han alcanzado el tipo de éxito financiero y el estatus social que simboliza el espacioso apartamento de Oberon en Park Avenue. Esto dista bastante de la autorrealización prevista por Maslow.

Para terminar, señalaré que dado que mi «amante potencial» estaba casada con algún tipo de hombre de negocios, y dado que ella misma había tenido algún tipo de carrera en el mundo de los negocios… No pude evitar pensar que el regreso de Oberón a su marido era una señal de la inutilidad de mi propia petición. A través de la película, los dioses intentaban decirme algo. En la versión francesa de la película que vi, el título era «Illusions perdues» (Ilusiones perdidas).

— Text(s) and artwork by William Eaton. The featured image is from a poster for the movie.

Teóricas y conceptos. Seguirá el mismo estilo que en el examen del bloque VI María

¿?